Human Trials the Courtroom Psychology Blog

Litigation and Clinical Psychologist, Adam Rosen, J.D., Ph.D., shares insights on jury psychology and winning in court from his consulting more than 400 cases over 25 years, surveying juries and mock juries, preparing witnesses, developing and sharpening winning case themes and interviewing jurors post-trial.

Doctor, Client, HERO!

The doctor’s care did not just “comply” with the standard of care – it EXCEEDED and EPITOMIZED it. This essential emphasis will deepen defense juror verdict commitment and prevent “plaintiff drift” in the jury room.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, upon your review of the evidence, I think you will conclude that my client, Dr. X, complied with the standard of ordinary, prudent health care that a professional with the same training and experience would provide under similar circumstances.”

While technically accurate, less inspiring words have rarely been spoken in a court of law, and they are, unfortunately, spoken in this way all too often. Though good facts will sometimes still save the doctor, counsel here has lost an opportunity to add value and has in fact set up a hazardous situation. It has left plaintiff-committed jurors as strong as ever and defense jurors under-motivated and vulnerable to “drift” to the plaintiff side.

Understatement, calm, and credibility are important qualities in a Trial Attorney and they are often held as a premium part of medical malpractice defense attorney’s reputation – with clients, insurance carriers, and opposing counsel. But these admirable traits must not preclude emphatic courtroom displays of conviction regarding the excellence of the defendant doctor’s choices and performance. Allowing understatement and calm to pervade the defense deprives jurors of the necessary information about the definitive adequacy of the doctor’s care – and this leaves a problematic array of juror verdict commitments as the group enters deliberations.

The Verdict Commitment Continuum

Medical malpractice cases, by definition, have substantial elements of sympathy for the plaintiff. It is rather unlikely to have zero plaintiff-leaning jurors in a group that has heard about birth injuries, missed heart attacks, lost loved ones, life-care plans, and the like.

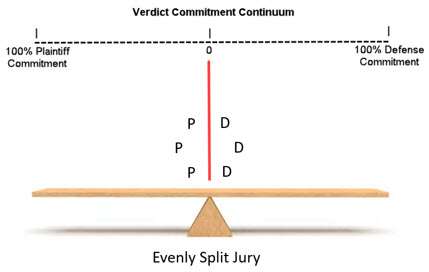

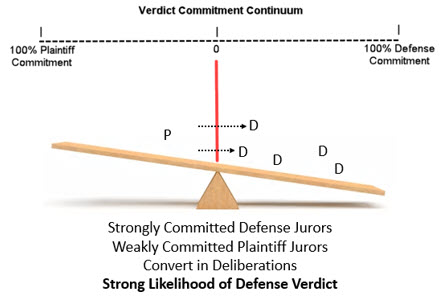

For these reasons, some jurors will naturally populate the plaintiff side of the verdict commitment continuum (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Verdict Commitment Continuum

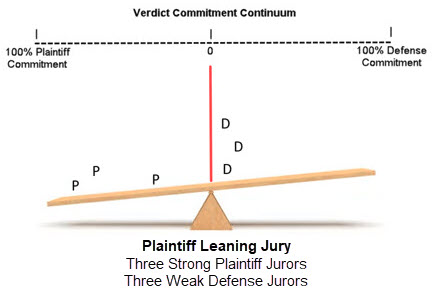

In a typical Med Mal case, some plaintiff jurors will be close to the crossover mid-line (0%) and some will be further out, closer to 100% plaintiff commitment. Defense jurors, however many there may be, also populate their side of the continuum in places closer or further from the crossover line. But a defense message that suggests only the mere adequacy of the doctor’s care, rather than its excellence – its certain compliance with the standard by dint of exceeding it (or epitomizing it) deprives defense-leaning jurors of any reason for their verdict commitment to be particularly strong. This then creates a hazardous combination – strongly committed plaintiff jurors and weakly committed defense jurors, dangerously close to the cross-over line, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Despite an “even” 3-3 split of plaintiff and defense jurors, the jury is plaintiff-leaning, even before deliberations.

The grouping of defense jurors close to the decision line creates an overall plaintiff-leaning group, even before the jury starts their deliberations.

Lest this becomes too abstract of an exercise, let’s ground this in the vernacular of a medical malpractice case, including the specific thoughts and feelings jurors can tend to have. Examples of the sentiments of plaintiff jurors may be as follows:

Plaintiff Juror: “I feel TERRIBLE for what this (woman, man, child, infant, family) has gone through and I really want to do something for them. And I am going to.” (Plaintiff Verdict Commitment > 50)

Plaintiff Juror: “I’m furious about the doctor letting this happen and barely doing what he was supposed to do.” (Plaintiff Verdict Commitment > 60)

Plaintiff-side emotion is often raw and it can feel deep and authentic and also, importantly, enlivening to the plaintiff juror. This can feel for many a juror to be one of the most meaningful situations they have been in for a long time – for some, ever. It is their chance to make a “real difference,” and they can be loathed to let the experience slip away.

On the other hand, defense jurors who have received the message above may be thinking as follows:

Defense Juror: “Sad situation, but I’m not really sure what the doctor did wrong as his lawyer said.” (Defense Verdict Commitment < 20)

Defense Juror: “The Judge said I’m not supposed to go with emotion and the lawyer said he met the standard of care – so that seems in favor of the doctor.” (Defense Verdict Commitment < 20)

The Problem of “Plaintiff Drift” With Low Commitment Defense Jurors

Take a moment to reflect on the above types of sentiments and then imagine the holders of these views encountering each other in the jury room. Which of the above groups seems more likely to resist change and which group seems like they’d be more willing to change sides?

Again, in the vocabulary of a legal case, consider possible subsequent sentiments of defense-leaning jurors after they have encountered their strong plaintiff counterparts in the jury room::

“Yeah, I can see that the doctor could have…” (pick any one of the following)

- “Sought a consult”

- “Done another EKG”

- “Admitted the patient”

- “Kept her in the hospital”

- “Initiated a cesarean”

. . so I can see how it might be okay to give them some money.”

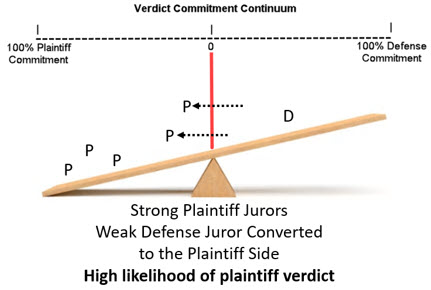

The problem of this type of “plaintiff drift,” where only modestly committed defense jurors to shift to the plaintiff side as the jury process drives for consensus (Figure 3), is both more likely and more hazardous if defense jurors begin deliberations in a place too close to the decision line (e.g. Verdict Commitment <20%).

Figure 3: Plaintiff Drift

This dynamic of “plaintiff drift” is much more likely to pertain when the defense counsel has more dispassionately asserted – and generally evidenced – the doctor’s mere compliance with the standard of care, rather than that the care either greatly “exceeded” the standard of care or that it firmly “epitomized” what was called for or reasonable with the information known at the time. This hazardous situation can be managed and changed through some highly accessible, but quite important rhetorical and stylistic adjustments.

Countering Plaintiff Drift With Justified Emphasis of Excellence in the Doctor’s Care

The common conception of winning by persuading more jurors can sometimes eclipse the more consequential impact of working to deepen the convictions of those jurors who are already on your side. This concurrent priority may often prove more effective in winning the verdict than focusing solely on winning more jurors over. We have seen above the hazard of having half of the jurors on your side, but only marginally so. Consider now the following statement from counsel about the excellence of the doctor’s care:

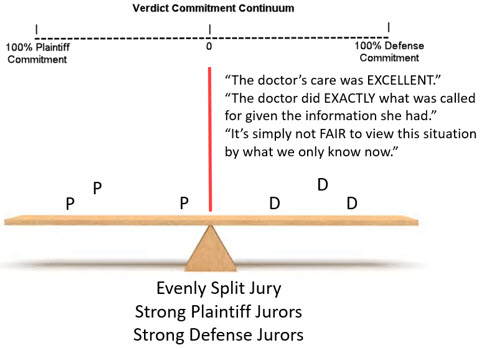

Lawyer B: “Ladies and gentlemen, as you heard and saw, by both the testimony of our expert, by Dr. Smith’s own testimony as well, the choices and procedures he made when he cared for Susan Johnson on July 14th – were exactly what the standard of care required of him and they were well within the standards and expectations of him. There was absolutely nothing about his choices that should have been any different given the information and options he had available to him at that time. For these reasons, it would only be just for you to find in favor of Dr. Smith when you retire to your deliberations in this matter.”

This type of sentiment – both overtly stated and also informing elements of questioning throughout the trial – will improve the pre-deliberation balance greatly. It will strengthen the convictions and commitments of defense learning jurors and significantly balance the scales with the plaintiff jurors (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Motivated Defense Jurors Balance the Scale

The distribution accomplished as depicted in Figure 4 is a much more promising one for the prospects of the defense. The hazard of weak defense jurors being converted has been made considerably less by virtue of the deepened convictions they adopt through the strength of the defense counsel’s statements.

Having now at least balanced the playing field against strong plaintiff jurors, the defense now at least has a fighting chance. And if counsel can also engage and temper the passions of fervent plaintiff jurors, (the subject of my next posting), an even more helpful distribution of juror commitments can arise. In that scenario (Figure 5), defense jurors have been deepened in their verdict commitments and have moved away from the center line, some degree further towards 100% defense verdict commitment. Plaintiff jurors, having felt understood and validated in their feelings, but then shown another path, can now bring themselves close to the midline and may then be brought over by deeply committed defense jurors during the deliberation process (as in Figure 5). As importantly, the now more strongly committed defense jurors are substantially less likely to convert to the other side.

Figure 5: Defense juror verdict commitment increased; plaintiff jurors were brought closer to the mid-line, where conversion by committed defense jurors become possible.

When we consider where we started this discussion, with fervent plaintiff jurors and weakly committed defense jurors, risking “plaintiff drift” and a plaintiff verdict (see Figure 2 and Figure 3), it is encouraging to know the determinants of this situation and the tools available to change the balance and protect our client, the responsible and effective health care provider.

Concepts Addressed in This Entry

- Verdict Commitment Continuum

- Plaintiff Drift

- Emphasize that care exceeded or epitomized the standard of care, rather than merely “complied” with it.

Our next entry will discuss the effective management of negative juror emotion in plaintiff jurors to reduce plaintiff verdict commitment (based upon negative emotions) going into deliberations. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

To receive updates about new entries in this blog, connect with Dr. Rosen on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/adamrosenjdphd-jury

To reach Dr. Rosen directly, call 617-921-0332 or e-mail arosen@juryassociates.com